Klingen

Introduction

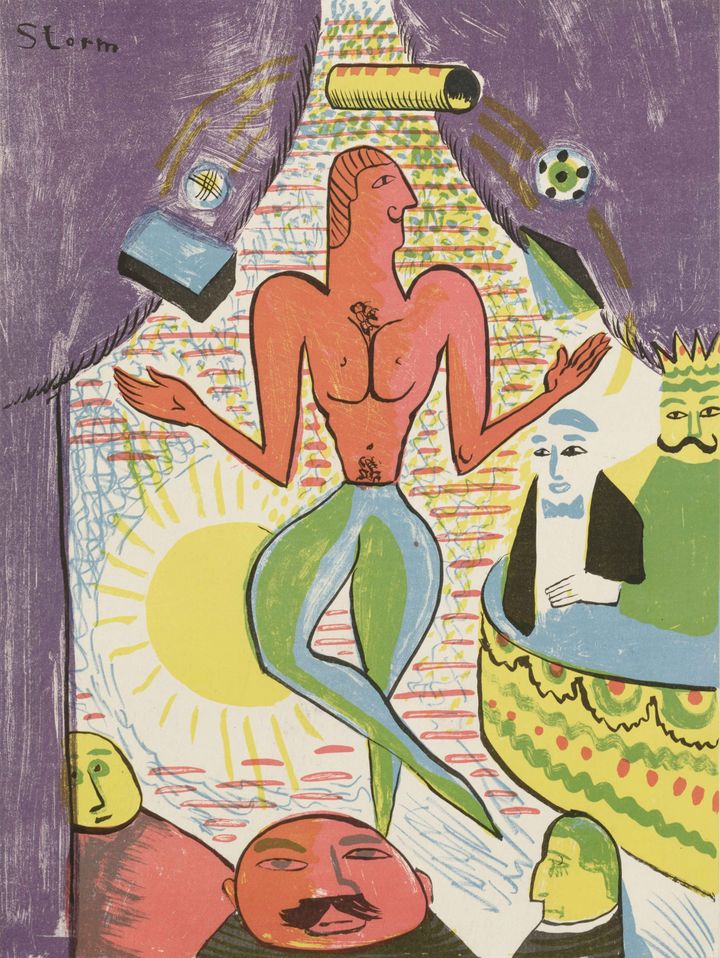

Klingen II, 9, p. 11. Chromolithograph by Robert Storm-Petersen.

The purpose of the journal Klingen (The Blade; 1917–20) was to show and explain what was happening in contemporary art and literature. With a primary focus on Danish developments, its outlook also extended to important current phenomena abroad. In pursuit of the additional ambition of promoting knowledge of graphic art, original graphic artwork was included from the outset. Over time, the issues featured a growing number of prints, which became increasingly riotous in expression and appeared in larger formats and in colour.

Klingen came out from October 1917 to September 1920 with one monthly issue, except for a few occasions, when two or even three issues were folded into one. The journal’s initiator, prime mover and economic backer was painter Axel Salto. In 1916, he had been on a prolonged visit to France, where he had met with Matisse and Picasso, among others, and generally caught up on current art trends. In the summer of 1917, Salto discussed his idea of launching a journal with his friend Poul Uttenreitter, who lived in Kerteminde, where painters Karl Isakson and Kurt Jungstedt also summered that year. After also discussing his plan with Vilhelm Wanscher, Mogens Lorentzen, Walt Rosenberg and Svend Johansen, Salto took action.

Poul Uttenreitter was Salto’s co-editor from the beginning. He was a lawyer but had many writers among his acquaintances and became the literary editor. From an early time, he was assisted in this task by Otto Gelsted, who also lived in Kerteminde and who was formally listed as co-editor from the second year of publishing. For the third annual volume, Emil Bønnelycke, Sophus Danneskjold-Samsøe and Poul Henningsen joined the editorial team.

Klingen became the mouthpiece and experimental lab of the modernists’ and the avant-garde. According to Axel Salto, the journal embraced anyone who wanted to help throw naturalism into the dustbin of history and replace inartistic mimicry of nature with ‘the “picture”, monumentality, the strictness and logical structure of the drawing’. The artists of Klingen had swagger, and with inspiration from military imagery they described themselves as ‘knights in the kingdom of beauty’ (Giersing) pushing forward like ‘a mighty phalanx’ (Salto).

Salto’s timing soon proved to be spot-on. In 1917, shortly after the release of the first issue of the journal, Kunstnernes Efterårsudstilling (the Artists’ Autumn Exhibition) debuted with the first exhibition in Denmark to showcase the full scope and radical character of contemporary Danish art. Spearheaded by Vilhelm Lundstrøm, Svend Johansen, Karl Larsen and Harald Giersing, the artists engaged in experiments inspired by cubism, futurism and expressionism and these movements’ rejection of the preceding tradition for depiction of the outside world. The results included pictures such as Karl Larsen’s Trappegang (Stairwell) from 1917, with collage elements under the paint and a dizzying spatial effect with expressionist influences, and Vilhelm Lundstrøm’s collages, such as Opstilling i en vindueskarm (Stil life on a window sill) from 1917, which featured various prefab elements, including two pieces of lace glued onto the canvas, giving the impression of a curtain. This marked a complete break from the oil painting’s coherent, illusionist universe and emphasized the picture as tangible object. To the audience, all familiar critical criteria appeared to have been suspended, and the new development set off years of intense debate in the press, with Klingen as a key participant.

Klingen soon became an arena, where passionate young artists could publish barrier-breaking works of poetry and graphic art, often created specifically for the journal, as well as critical and theoretical essays in support of the radical new movement. Klingen had a broad scope and was at once diverse, open-minded and sharply polemic. It was also a journal whose profile and centre of gravity shifted over the course of its three-year existence, its content shaped, to a high degree, in dialogue with developments in the turbulent art scene and public debate at the time, including the extensive ‘dysmorphism debate’, which discussed whether modern art was a symptom of some sort of infectious mental illness.

There are no actual manifestos or stringent programmes in Klingen. In visual art, the emphasis was on radical renewal and on re-establishing the connection with the art tradition that preceded naturalism. The latter, in the modernists’ opinion, had reduced art to the mere depiction of nature, ‘palette tricks’ and ‘virtuosity’. To overcome this, they wanted to rediscover past eras’ greater knowledge of image composition. They also claimed the right to seek inspiration anywhere, without limitations in terms of geography or time. As the modernists saw it, modern methods of communication and reproduction had opened a host of new possibilities that rendered the traditional perception of ‘schools’ and ‘academies’ obsolete. There was intense debate about where art should seek its primary source of renewal. Some pointed to primitive art as an eye-opener; others argued that inspiration should be found in feats of modern engineering and other visual phenomena of industrial society, the rapid pace of the 20th century or the new possibilities of imagery made possible by modern press photography – the snapshot. These proposals coexisted with the recurring claim of the autonomy of art and the legitimacy of striving for an expression of the artist’s soul rather than a depiction of nature.

Among the literary contributors to the journal were Johannes Buchholtz, Fredrik Nygaard, Tom Kristensen, Norwegian poet Alf Larsen and the editors, Otto Gelsted and Emil Bønnelycke. Their contributions ranged from Buchholtz’s and Gelsted’s lyrical nature poetry to Bønnelycke’s and Nygaard’s expressive and exalted poems celebrating technology and the modern city. In Bønnelycke’s case, the poems were supplemented with experiments that transcended the boundary between literature and painting, both in his graphic poem Berlin and in calligrams that mixed words and images in the style of the French poet Guillaume Apollinaire.

Klingen drew inspiration from many of the modernist and avant-garde journals that were published throughout most of Europe during this time, often spanning across media and art forms, such as the German journal Der Sturm, the French journals L’Élan and Sic and, perhaps especially, the Swedish journal flamman. The latter premiered in January 1917 and was shown to the printer of Klingen, Chr. Cato, for inspiration. When flamman failed to survive as a monthly publication beyond 1917, it was decided that Klingen should target all of Scandinavia. This was announced in the final issue of the volume 1, and from volume 2, contributions from other Scandinavian countries, which had been part of the journal’s profile from the beginning, became more numerous. However, a plan to have the editorial team alternate between the Scandinavian countries was never realized.

The journal never made a profit, so when Axel Salto’s inheritance, which had provided the initial capital, as well as additional collateral from stockbroker William Gasmann, which enabled the journal to continue past its second year, had been depleted, the journal closed. However, the name and the spirit did not disappear entirely. Some of the partners behind the publication – Axel Salto, Svend Johansen, Vilhelm Lundstrøm and Karl Larsen – formed the artist association De Fire (The Four), known until the mid-1920s as De Fire. Klingens Udstilling (The Four: Klingen’s Exhibition). Another group that emerged after the closure of the journal was Klingens grafiske Forening (Klingen’s Graphic Association). During the 1920s, the latter group, consisting of three of the former editors – Axel Salto, Poul Uttenreitter and Poul Henningsen – published portfolios with graphic art by some of the artists who had contributed to the journal.

Poul Uttenreitter’s Archives

Because the editors lived so far apart – in Copenhagen and Kerteminde, respectively – their work on the journal required extensive correspondence. Thanks to Poul Uttenreitter, many of these letters have been preserved. The digitized and annotated letters included here come from two archival collections at the Royal Danish Library:

- Tilg. 634. Poul Uttenreitters papirer. Breve især vedr. Klingen, adresseret også til Axel Salto og Otto Gelsted (Poul Uttenreitter’s papers: Letters mainly regarding Klingen, also addressed to Axel Salto and Otto Gelsted)

- NKS 4722, 4˚. Breve til Poul Uttenreitter (Letters to Poul Uttenreiter)

The selection from these archival collections includes letters that primarily concern Klingen, the lavish books that were published concurrently with the journal and correspondence concerning Klingens grafiske Forening. ‘Tilg. 634’ contains the most comprehensive collection of material related to Klingen and will be digitized and published first. Next follows ‘NKS 4722, 4˚’, a large collection of letters with a minor amount of material related to Klingen.